Baby Born With Blisters on Skin and Eyes Crossed

Skip Nav Destination

Diagnostic Dilemmas | March 01 2018

Well-Appearing Newborn With a Vesiculobullous Rash at Nativity

Sarah E. Stewart, MD;

aDivisions of General Pediatrics,

Address correspondence to Sarah E. Stewart, Medico, Partition of Full general Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, Lucile Packard Children'south Hospital, 725 Welch Rd, Mail Code 5906, Palo Alto, CA 94304. Electronic mail: sarahs12@stanford.edu

Search for other works by this author on:

Jody L. Lin, MD;

bPediatric Hospital Medicine, and

Search for other works by this author on:

Trung H. Pham, MD;

cPediatric Infectious Diseases, Department of Pediatrics, Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford, Palo Alto, California; and

Search for other works by this author on:

Ann L. Marqueling, MD;

dDepartments of Dermatology,

eastwardPediatrics, and

Search for other works by this author on:

Kerri East. Rieger, Dr.;

dDepartments of Dermatology,

fPathology, Schoolhouse of Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, California

Search for other works by this author on:

Address correspondence to Sarah E. Stewart, Medico, Division of General Pediatrics, Section of Pediatrics, Lucile Packard Children's Hospital, 725 Welch Rd, Mail Lawmaking 5906, Palo Alto, CA 94304. E-mail: sarahs12@stanford.edu

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF Interest: The authors have indicated they take no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Financial DISCLOSURE: Dr Lin received back up from the KL2 Mentored Career Development Laurels of the Stanford Clinical and Translational Scientific discipline Award to Spectrum (NIH KL2 TR 001083, UL1 TR 001085) and the Clinical Excellence Research Heart; the other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Pediatrics (2018) 141 (three): e20170236.

A term, appropriate-for-gestational-age, male baby born via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery presented at birth with a full-body erythematous, vesiculobullous rash. He was well-appearing with normal vital signs and hypoglycemia that quickly resolved. His father had a history of herpes labialis. His mother had an episode of canker zoster during pregnancy and a prolonged rupture of membranes that was adequately treated. The patient underwent a sepsis workup, including two attempted but unsuccessful lumbar punctures, and was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics and acyclovir, given concerns about bacterial or viral infection. The rash evolved over the grade of several days. Subsequent workup, with item attention to his history and presentation, led to his diagnosis.

Instance History With Subspecialty Input

Dr Sarah Stewart (Pediatrics, Showtime-Year Resident)

The patient was a term, advisable-for-gestational-age, male baby born via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery who presented at nascency with a total-body rash. The rash appeared as lengthened discrete erythematous papules and plaques with occasional overlying fluid-filled vesicles and bullae, nigh prominent on the face and scalp but sparing mucous membranes, palms, and soles (Figs 1 and ii). He was well-appearing with normal vital signs, Apgar scores of 8 and nine, a nativity weight of 3768 thousand, and an test with results that were otherwise normal. His mother's pregnancy was remarkable for presumed herpes zoster at 31 weeks that resolved with valacyclovir. She had a history of primary varicella-zoster at 2 years of age and 2 episodes of herpes zoster before this pregnancy. Labor and delivery were complicated past a prolonged rupture of membranes (20 hours) and meconium-stained fluid. Though maternal prenatal laboratory tests were negative for infection, the patient's mother received 3 doses of clindamycin because of a history of previous neonatal group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection. The patient'due south father had a history of herpes labialis. The patient's mother denied any history of herpes labialis or herpes genitalis.

FIGURE one

Patient on first day of life. Coalescing erythematous vesicles are seen on the face up, and dull gray and erythematous patches and plaques are seen on the torso and extremities. The mucous membranes, hands, and the soles of the anxiety are spared.

Effigy i

Patient on offset day of life. Coalescing erythematous vesicles are seen on the face up, and dull gray and erythematous patches and plaques are seen on the body and extremities. The mucous membranes, easily, and the soles of the feet are spared.

Figure 2

A, Lesions on the first day of life. B, New lesions on fingers on the fourth day of life. C, New lesions on cheeks on the fourth day of life. D, Lesions on the fifth 24-hour interval of life. The forehead vesicles became less raised and less erythematous. A few new lesions appeared on the scalp.

Effigy ii

A, Lesions on the first day of life. B, New lesions on fingers on the fourth day of life. C, New lesions on cheeks on the fourth day of life. D, Lesions on the fifth day of life. The forehead vesicles became less raised and less erythematous. A few new lesions appeared on the scalp.

The patient's initial laboratory results at ii hours of life included a white blood cell count of 24.four K/µL (normal: 7.5–30.0 Yard/µL) with 74% neutrophils (normal: 32.0%–68.0%), 20% lymphocytes (normal: 24.0%–36.0%), iv% monocytes (normal: 0.0%–0.nine%), 1% eosinophils (normal: 0.0%–2.0%), and 0% basophils (normal: 0.0%–1.0%); a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 0.03 mg/dL (normal: 0.00–0.99 mg/dL); a blood glucose level of 32 mg/dL (normal: 45–110 mg/dL); an aspartate aminotransferase level of 68 IU/Fifty (normal: 15–41 IU/Fifty); an alanine transaminase level of 8 IU/L (normal: xi–63 IU/L); a total bilirubin level of 3.1 mg/dL (normal: 2.0–6.0 mg/dL); and an alkaline phosphatase level of 110 IU/Fifty (normal: thirty–300 IU/L). The remaining results of the complete blood cell (CBC) count and comprehensive metabolic panel were unremarkable.

Dr Hilgenberg, every bit a pediatric hospitalist assuming care of this babe subsequently nativity, what is your differential diagnosis?

Dr Hilgenberg (Pediatric Hospitalist)

This infant's presentation is nearly concerning for one of the following: (i) a congenital "TORCH" infection, which is an infection acquired by toxoplasmosis, other pathogens (varicella-zoster virus [VZV], syphilis, enteroviruses, or parvovirus B19), rubella, cytomegalovirus, or herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1 ; (2) bacterial sepsis, given the mother's previous neonatal GBS infection with her last pregnancy ii ; and (3) a primary dermatologic condition such as epidermolysis bullosa (EB).

Dr Stewart

How and when do TORCH infections typically present? What, if whatever, are their dermatologic manifestations, given that peel lesions are our patient's but sign of illness?

Dr Hilgenberg

Interestingly, the majority of live-born infants with TORCH infections are asymptomatic at birth. iii When symptomatic, common features can include microcephaly, intrauterine growth restriction, jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, intracranial calcifications, and rash, besides as laboratory abnormalities. Despite these common features, some clinical manifestations are more suggestive of particular infections in the neonate.

For case, congenital toxoplasmosis has 4 subtypes: subclinical, severe neonatal disease, mild or astringent disease in the start few months of life, and sequelae or relapse of an undiagnosed, typically ocular, infection later in childhood. The minority of patients who are symptomatic at birth may present with the archetype triad of chorioretinitis, hydrocephalus, and intracranial calcifications. Dermatologic features include a maculopapular, petechial, or purpuric rash. 1 , iii Additional signs and symptoms include fever, seizures, generalized lymphadenopathy, thrombocytopenia, mononuclear cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis, or elevated cerebrospinal fluid protein. The incidence of congenital toxoplasmosis in the United states of america is one in 1000 to 1 in 10 000 newborns. 4

Built syphilis is characterized as either early, presenting before 2 years of age just typically within the first 5 weeks of life, or late, presenting after 2 years of age. Differentiating findings amongst infants with early congenital syphilis include nasal belch, maculopapular rash (specially on the palms, soles, and diaper surface area), generalized lymphadenopathy, and skeletal abnormalities. Patients with late congenital syphilis nowadays with physical anomalies, such as teeth or bony abnormalities, simply rarely present with rash. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that the incidence of congenital syphilis in the United States is 11.half dozen cases per 100 000 newborns. five

Congenital rubella syndrome tin can include sensorineural hearing loss, ocular affliction (cataracts, congenital glaucoma), cardiac defects, os affliction, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, "blueberry muffin rash," or petechiae and purpura caused by dermal erythropoiesis. 3 After the development of the rubella vaccine in 1969 and widespread employ presently thereafter, the incidence of congenital rubella in the U.s.a. is <1 case per year. 6

Cytomegalovirus, the most common built viral infection in the United States, with an incidence of 0.5% to 1.0% in all newborns, causes symptoms at birth in 10% of infected infants. vii Differentiating clinical features may include sensorineural hearing loss, periventricular intracranial calcifications, chorioretinitis, seizures, thrombocytopenia, and rash with a petechial, morbilliform, or widespread erythematous, macular advent.

Congenital HSV infection is relatively rare, with an incidence of 1 in 3000 to i in xx 000 newborns, and infants may exhibit the characteristic triad of pare findings (scarring, active lesions, hypo- and hyperpigmentation, aplasia cutis, and/or an erythematous macular exanthem), eye harm, and severe central nervous system (CNS) manifestations. 8 , 9 Near newborns with perinatally caused HSV announced normal at birth and then present within the first one to 6 weeks of life with infection symptoms localized to the skin, eyes, and mouth (SEM), involving the CNS, or disseminated.

Congenital varicella may present with cicatricial skin lesions, which may be pigmented or depressed in a dermatomal distribution, ocular disease, limb abnormalities, and cortical atrophy or seizures. If present, the rash in both HSV and VZV is vesicular in nature. The Centers for Disease Command and Prevention reports that the incidence of congenital varicella in the United States is 0.4% to two.0% of newborns born to mothers with varicella in the commencement or second trimester. Neonatal varicella, a much more severe and oftentimes life-threatening condition, tin can occur when the mother develops varicella in the time menses 5 days before the delivery through 2 days after delivery. x

Parvovirus B19 tin present with ocular anomalies, hydrocephalus, musculoskeletal problems, hepatocellular damage, heart defects, and subcutaneous edema, also as petechiae. iii

Dr Stewart

How does the rest of your differential diagnosis inform the next steps in this infant's direction?

Dr Hilgenberg

Bacterial sepsis, well-nigh commonly acquired by GBS in the neonatal period, typically presents within the first 24 to 48 hours of life and is associated with low birth weight, hypothermia, lethargy, poor feeding, and an elevation of CRP levels. Respiratory distress and cardiac symptoms may be nowadays if these organ systems are involved. Cutaneous manifestations are less common, but they can occur. 11

The fact that our patient is overall well-appearing and well-developed with normal vital signs and without significant laboratory abnormalities argues against a congenital TORCH infection or bacterial sepsis. His rash is not typical of those seen in toxoplasmosis, syphilis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, or parvovirus B19. Therefore, I would send blood and lesion cultures to test for bacteria and HSV/VZV polymerase concatenation reactions (PCRs). Though the patient appears hemodynamically stable, meningitis is a potentially devastating issue of TORCH infections and bacterial sepsis, so lumbar puncture should be considered. I would be inclined to start empirical treatment with wide-spectrum antibiotics for possible bacterial sepsis and antiviral agents for possible HSV or VZV. Lastly, I would consider a dermatology consultation, depending on how the clinical course evolves.

Dr Stewart

The patient underwent a sepsis workup. Lumbar puncture was attempted and unsuccessful. A lesion bacterial civilisation and serum and lesion HSV/VZV PCRs were obtained. The patient was started on intravenous ampicillin, gentamicin, and acyclovir. He was feeding, urinating, and stooling normally with a continued overall well appearance.

Dr Pham, as a pediatric infectious illness specialist, what are you nearly concerned near, given this patient's presentation and history? Are there other studies you would recommend?

Dr Pham (Pediatric Infectious Illness)

The patient has been well-appearing and neurologically appropriate with normal vital signs despite the all-encompassing rash. His CBC panel, CRP test, liver function test (LFT), and blood civilization results are reassuring to date. In terms of infectious etiologies, the differential diagnosis for a diffuse vesiculobullous rash in newborns, as seen in this patient, would include viral infections such equally HSV and VZV, staphylococcal and streptococcal skin infections, listeriosis, congenital candidiasis, and congenital syphilis. 12

Neonatal HSV infection seems unlikely, given how early the lesions appeared (at birth) and given his lack of systemic symptoms with this level of cutaneous severity. Approximately 85% of HSV infections in newborns are transmitted intrapartum, and x% are transmitted postnatally. 13 Congenital or intrauterine HSV infection is very rare, accounting for only ∼5% of neonatal cases, and is often accompanied past congenital malformations, which our patient does not appear to accept. 13 , 14 Every bit Dr Hilgenberg pointed out, clinical manifestations of neonatal HSV infections usually fall into three disease types: SEM illness, CNS disease, and disseminated disease. SEM disease accounts for 45% of cases and typically presents at x to fourteen days of life. xv , – 17 Skin manifestations typically include small clustered vesicles with surrounding erythema that mature into pustules and then erosions with overlying eschar germination over 1 to iii days. Lesions begin at the site of inoculation, virtually commonly at sites of skin injury or prolonged contact with the neck, and take the potential to spread locally or disseminate more than broadly. In dissimilarity, built HSV commonly presents with vesicles at birth. Cutaneous scars oftentimes are also present. 18 CNS disease represents thirty% of cases, with onset at ∼16 to 19 days. Disseminated disease, accounting for the remaining 25%, ordinarily presents at seven to 12 days, with many cases at <7 days. 17 Yet, newborns with disseminated HSV infections are frequently critically ill, and threescore% to 75% have CNS involvement. 13 , 17

VZV is also unlikely because the patient's mother has a history of master varicella in early childhood, corroborated by her history of subsequent episodes of zoster. Thus, her dermatomal eruption during pregnancy should reverberate a localized reactivation of VZV rather than a primary varicella infection, which would have put the infant at risk for congenital or neonatal VZV transmission. Viremia from VZV reactivation has only been reported on rare occasions in immunocompromised individuals who have disseminated disease. Evidence linking zoster during pregnancy with built varicella is lacking. 19 , 20

Staphylococcal and streptococcal pare infection, listeriosis, and built candidiasis are possible; even so, given the extensive skin manifestation, it would be unusual to have such a well-actualization infant with normal vital signs and benign laboratory results. Lastly, congenital syphilis is also less likely, because the maternal syphilis screen during pregnancy had negative results and because the infant, apart from the rash, has no other clinical manifestations suggestive of syphilis.

In terms of management, empirical coverage with acyclovir, principally for HSV at this bespeak, is prudent while the patient is existence worked upwardly for neonatal HSV. 9 However, our suspicion of HSV, specially of CNS and disseminated disease, is low. Thus, nosotros do non recommend repeating lumbar puncture at this point. We hold with obtaining HSV and VZV PCRs from blood and HSV PCRs from the conjunctivae, nares, oropharynx, and rectum. In addition, nosotros recommend that HSV/VZV PCRs, a Gram-stain, a bacterial civilisation, a potassium hydroxide stain, and a fungal civilisation be obtained from the lesions. An ophthalmology exam to complete the workup for TORCH infections, including neonatal HSV disease, should too exist performed. The patient has been on ampicillin and gentamicin, empirically, for bacterial sepsis. Given the lack of signs and symptoms suggestive of sepsis, it would be reasonable to discontinue empirical antibiotics if the blood civilisation is negative for leaner at 48 hours. Lastly, information technology is important to consider noninfectious etiologies for this rash, such as primary dermatologic atmospheric condition.

Dr Stewart

Dr Pham, would y'all recommend starting varicella-zoster immune globulin (VariZIG) for possible varicella?

Dr Pham

We would not recommend VariZIG at this point. Based on maternal history and timing of clinical presentation, our suspicion of primary varicella in this infant is low. Required criteria for VariZIG administration are significant exposure to varicella (such equally existence an exposed newborn) and inclusion in one of the following populations: (ane) immunocompromised children, (two) meaning women without evidence of immunity, (3) newborns whose mothers had an onset of chickenpox between 5 days before delivery and 48 hours after delivery (VariZIG is not indicated if the mother has zoster), (four) hospitalized premature infants of ≥28 weeks' gestation whose mothers lack amnesty against VZV, and (5) hospitalized premature infants of <28 weeks' gestation or with a birth weight of 1000 chiliad or less, regardless of maternal immunity. xviii , 21

Dr Stewart

A pediatric ophthalmologist was consulted and found no evidence of conjunctivitis, keratitis, cataracts, optic nerve swelling, chorioretinitis, or uveitis. Over the next 72 hours, new similar lesions appeared on the baby'south confront, scalp, hands, and feet. The older lesions became tedious and flat. A pediatric dermatologist was consulted.

Dr Marqueling, equally a pediatric dermatologist, what is your differential diagnosis for this rash?

Dr Marqueling (Pediatric Dermatology)

In addition to the communicable diseases etiologies, bullous diseases presenting in the neonatal period should be considered. In particular, I am concerned about bullous mastocytosis, given the vesicles and modest bullae with overlying erythematous and edematous papules and plaques and the questionably present Darier's sign on my examination. Bullous lesions in cutaneous mastocytosis commonly develop within erythematous papules or plaques on involved skin. Other weather condition I would include in my differential diagnosis, though extremely uncommon, are chronic bullous disease of childhood (linear immunoglobulin A affliction), EB (including bullous dermolysis of the newborn), and epidermolytic ichthyosis. Chronic bullous disease of babyhood is a rare autoimmune bullous disease that typically presents at 1 to 6 years of age with widespread, tense, bullae-forming rosettes. Rare reports of neonatal presentation with bullae at nativity accept been reported. 22 EB is a grouping of inherited disorders characterized by skin fragility. Although severity subsequently in life varies by blazon of EB, neonatal presentation may be similar in all types, presenting with generalized mechanically-induced blisters and erosions. Boosted features may include absent or dystrophic nails and cutaneous localized absences of pare (big ulcers on the lower extremities, each with well-demarcated edges and a red, shiny base). Epidermolytic ichthyosis may nowadays in ways that are almost indistinguishable from EB, with spontaneous or mechanically-induced bullae as the nearly prominent characteristic. Features that may help to differentiate the ii conditions include a thickened, ruddy, and macerated base with bullae or raw denuded areas. Incontinentia pigmenti besides crossed my heed, simply every bit this is X-linked ascendant trait, it is usually non uniform with life in male person fetuses. 23 , 24

Dr Stewart

You mention Darier's sign. What is this, and what implication does this possible finding accept for our patient?

Dr Marqueling

Darier'south sign is said to exist present when the skin urticates, becoming edematous and red, similar to a hive, after stroking it with a blunt object. It is caused by the release of histamine from mast cells and is seen in weather condition such as mastocytosis.

Dr Stewart

Do you have boosted recommendations regarding diagnostic workup, given your concerns and exam findings?

Dr Marqueling

I would follow-up on blood and lesion cultures and PCRs and proceed acyclovir until viral PCR results returned. Given my concern for possible bullous mastocytosis or a neonatal baking disorder, I recommend a pare biopsy.

Dr Stewart

After 48 hours, all cultures and PCRs were negative for infection, so anti-infectives were discontinued. A pare biopsy was performed. Dr Reiger, can you lot draw your findings?

Dr Rieger (Dermatopathologist)

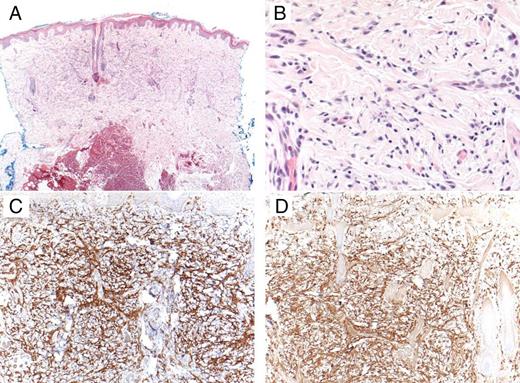

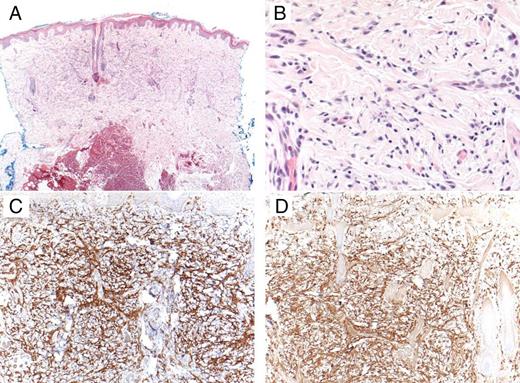

A skin biopsy showed an infiltrate of monomorphic cuboidal and fusiform cells in the upper third of the dermis (Fig 3). At that place was a mild superficial dermal edema, merely there was no prove of a subepidermal split. The cells in the infiltrate contained small central nuclei and lightly granular amphophilic cytoplasm, and they stained positive for CD117 and the mast cell tryptase, confirming the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis. The mast cells did non express CD25. The expression of CD25 on cutaneous mast cells from developed patients with urticaria pigmentosa has been shown to be predictive of systemic mastocytosis, although this has not been studied in the pediatric population. 25 Regarding the other diagnoses on the differential, no viral cytopathic changes were identified, and an immunostain for HSV had negative results, providing no support for a herpetic infection. No neutrophilic infiltrate or subepidermal separate were identified to support chronic bullous disease of babyhood. No blister was identified to support an inherited blistering disease. Thus, overall, this skin biopsy was uniform with cutaneous mastocytosis.

FIGURE three

A dial biopsy showed an infiltrate filling the upper third of the dermis. The infiltrate was composed of monomorphic spindled and cuboidal cells with small-scale cardinal nuclei and lightly granular amphophilic cytoplasm. A, Hematoxylin and eosin stain (original magnification ×4). B, Hematoxylin and eosin stain (original magnification ×40). C, Mast cell marker CD117 (original magnification ×10). D, Mast cell tryptase (original magnification ×x).

Effigy iii

A punch biopsy showed an infiltrate filling the upper third of the dermis. The infiltrate was equanimous of monomorphic spindled and cuboidal cells with small central nuclei and lightly granular amphophilic cytoplasm. A, Hematoxylin and eosin stain (original magnification ×4). B, Hematoxylin and eosin stain (original magnification ×40). C, Mast cell marker CD117 (original magnification ×10). D, Mast jail cell tryptase (original magnification ×ten).

Dr Marqueling, what is mastocytosis?

Dr Marqueling

The mastocytoses are disorders characterized by mast cell aggregating in tissues throughout the body. They are caused by a mutation in the c-tyrosine-kinase factor. Information technology is estimated that <200 000 people full in the United States are affected. 26 Severity ranges from cutaneous to systemic disease. 27 Cutaneous mastocytosis accounts for ∼50% of cases, occurs primarily in children, and presents most often shortly later birth, with 80% of cases occurring earlier age 2 and l% of cases resolving past adolescence. 26 , 28 The most common form is a solitary mastocytoma, presenting as a single tan to brown papule or small plaque. Infants with multiple lesions, ranging from a few to a couple hundred, are diagnosed with urticaria pigmentosa. In the nigh severe form, diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis, patients have virtually confluent erythema with a crude peau d'orange texture. When mast cells are stimulated, they may degranulate and release histamine, causing lesions of mastocytosis to become raised, or in some cases, to blister. A definitive diagnosis is made past confirming the presence of an aggregating of mast cells on skin biopsy. 28 Darier's sign, as described to a higher place, is common. 27 Serum tryptase, a marker of overall mast cell brunt, is often elevated in more than widespread cases.

Dr Stewart

Given the extent of our patient'south cutaneous interest, are you concerned about systemic involvement? If so, what studies and handling might exist indicated?

Dr Marqueling

Although the bullous presentation is striking, the number and relatively discrete nature of his plaques places him into the category of urticaria pigmentosa, as opposed to the more astringent diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis. With the more than common forms of babyhood mastocytosis, lone mastocytoma and urticaria pigmentosa, at that place is rarely systemic involvement. Unlike adult-onset mastocytosis, internal organ interest is rare simply tin exist severe when nowadays.

Although the patient has had no diarrhea and no show of hepatosplenomegaly, a liver ultrasound would be prudent. I besides recommend a CBC count to evaluate for bone marrow involvement. Finally, I would obtain a serum tryptase level, which is more than likely to be elevated in patients with systemic illness. If lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or sick-advent are nowadays, evaluation for systemic mastocytosis should include a CBC console, LFTs, and, potentially, an abdominal ultrasound, a bone scan, and a bone marrow biopsy. A CBC panel, LFTs, and abdominal ultrasound were conducted for this patient and yielded normal results. The authors of a 20-yr retrospective written report take suggested that the results of a bone marrow biopsy, if normal, were predictive of resolution of pediatric mastocytosis if presenting before the historic period of ii and, if abnormal, might predict progression to ongoing systemic mastocytosis. 29 A bone marrow biopsy would not change the treatment of this patient at this time because he currently has no signs of systemic involvement, so I recommend deferring it. Treatment of systemic mastocytosis includes biologics such as interferon-α-2b and tyrosine-kinase inhibitors and should be started at signs of systemic involvement. 30

Dr Stewart

What do y'all recommend for our patient's management now that we accept a diagnosis?

Dr Marqueling

In terms of handling, I recommend starting the histamine receptor blockers cetirizine (an oral histamine one receptor antagonist with a long runway record of safety in infants) and ranitidine (an oral histamine ii receptor antagonist, which as well protects confronting gastric hypersecretion because of the increased number of mast cells in the breadbasket). 31 For topical handling, I recommend topical cromolyn, a mast prison cell stabilizer, for existing airtight lesions to endeavor to prevent formation of urticarial lesions and bullae. I likewise recommend mupirocin 2% ointment, a topical antibiotic, for open and exposed lesions, and triamcinolone 0.1% ointment, a topical corticosteroid, to decrease skin inflammation. Patients should have fix admission to injectable epinephrine because of the increased risk of anaphylaxis; parents should be educated on when and how to utilise it.

Information technology is mutual for mastocytosis to involute in childhood, but some cases persist until puberty. Nosotros discussed this entity at length with the patient'southward parents, and discussed the potential triggers and/or mast cell degranulators that should exist avoided, such equally physical stimuli (friction, pressure, and scratching lesions), medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opiates, codeine, and polymyxin), and foods (citrus, strawberries, tomatoes, spinach, specific cheeses, egg whites, and sure fish).

Dr Stewart

Dr Marqueling'south treatment recommendations were initiated, and the patient was discharged from the infirmary. How is the patient doing now?

Dr Hilgenberg

At 2 years of historic period, he is doing well. He had 1 visit to the emergency department at 5 months of historic period for hematemesis and melena presumed to be caused by Mallory Weiss tears secondary to gastric hypersecretion. Haemorrhage resolved with omeprazole, and he is at present maintained on ranitidine and cromolyn sodium. His lesions are now primarily hyperpigmented with almost complete resolution of blistering. For the lesions, he receives topical cromolyn daily and topical steroids as needed. He has an epinephrine autoinjector with him at all times just has never needed to use it. Because his laboratory work remains normal, indicating at that place is no systemic interest, he has non had a os marrow biopsy to evaluate for hematologic involvement. He continues to abound and develop normally.

-

CBC

-

CNS

-

CRP

-

EB

-

GBS

-

HSV

-

LFT

-

PCR

polymerase chain reaction

-

SEM

-

TORCH

toxoplasmosis, other, rubella, cytomegalovirus, or herpes

-

VariZIG

varicella-zoster immune globulin

-

VZV

Dr Stewart contributed to the conception and design of the case presentation, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Lin and Everhart contributed to the conception and design of the case presentation and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Pham, Marqueling, and Reiger drafted their sections of the initial manuscript and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Hilgenberg contributed to the conception and design of the case presentation, drafted portions of the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FUNDING: No external funding.

References

i

Del Pizzo J

Focus on diagnosis: congenital infections (TORCH).

Pediatr Rev

.

2011

;

32

(

12

):

537

–

542

2

Polin RA Commission on Fetus and Newborn

Management of neonates with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis.

Pediatrics

.

2012

;

129

(

five

):

1006

–

1015

three

Neu N Duchon J Zachariah P

TORCH infections.

Clin Perinatol

.

2015

;

42

(

ane

):

77

–

103, viii

4

American University of Pediatrics Kimberlin DW Brady MT Jackson MA Long SS

Red Book: 2015 Study of the Committee on Infectious Diseases

.

Elk Grove Village, IL

:

American Academy of Pediatrics

;

2015

:

787

–

796

5

Bowen V Su J Torrone E Kidd S Weinstock H

Increase in incidence of congenital syphilis - United States, 2012-2014.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep

.

2015

;

64

(

44

):

1241

–

1245

vii

American University of Pediatrics Kimberlin DW Brady MT Jackson MA Long SS

Crimson Book: 2015 Report of the Committee of Infectious Diseases

.

Elk Grove Village, IL

:

American University of Pediatrics

;

2015

:

317

–

322

8

Kimberlin DW

Neonatal herpes simplex infection.

Clin Microbiol Rev

.

2004

;

17

(

one

):

1

–

thirteen

9

American Academy of Pediatrics Kimberlin DW Brady MT Jackson MA Long SS

Blood-red Book: 2015 Written report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases

.

Elk Grove Village, IL

:

American Academy of Pediatrics

;

2015

:

432

–

445

eleven

Verani JR McGee Fifty Schrag SJ Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease--revised guidelines from CDC, 2010.

MMWR Recomm Rep

.

2010

;

59

(

RR-10

):

1

–

36

12

Hussain South Venepally M Treat JR

Vesicles and pustules in the neonate.

Semin Perinatol

.

2013

;

37

(

i

):

8

–

15

13

Wilson CB Nizet V Maldonado YA Remington JS Klein JO

Remington and Klein's Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant

. 8th ed.

Philadelphia, PA

:

Saunders

;

2016

14

Baldwin S Whitley RJ

Intrauterine canker simplex virus infection.

Teratology

.

1989

;

39

(

ane

):

1

–

10

15

Kimberlin D Lin C Jacobs RF

Natural history of neonatal herpes simplex virus infections in the acyclovir era.

Pediatrics

.

2001

;

108

(

2

):

223

–

229

sixteen

Corey L Wald A

Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections.

N Eng J Med

.

2009

;

361

(

14

):

1376

–

1385

17

Curfman AL Glissmeyer EW Ahmad FA

Initial presentation of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection.

J Pediatr

.

2016

;

172

:

121

–

126.e1

18

Friedlander S Bradley J

Viral Infections

. In: Eichenfield L Frieden I Esterly Due north

Neonatal Dermatology

, 2nd ed.

Philadelphia, PA

:

Saunders

;

2008

:

193

–

212

19

Feldman S Chaudary S Ossi M Epp East

A viremic phase for herpes zoster in children with cancer.

J Pediatr

.

1977

;

91

(

iv

):

597

–

600

20

Enders Chiliad Miller E Cradock-Watson J Bolley I Ridehalgh K

Consequences of varicella and herpes zoster in pregnancy: prospective study of 1739 cases.

Lancet

.

1994

;

343

(

8912

):

1548

–

1551

21

American Academy of Pediatrics Kimberlin DW Brady MT Jackson MA Long SS

Red Book: 2015 Report of the Commission of Infectious Diseases

.

Elk Grove Village, IL

:

American Academy of Pediatrics

;

2015

:

846

–

860

22

Hruza LL Mallory SB Fitzgibbons J Mallory GB

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis in a neonate.

Pediatr Dermatol

.

1993

;

x

(

ii

):

171

–

176

23

Howard R Frieden I

Vesicles, Pustules, Bullae, Erosions and Ulcerations

. In: Eichenfield L Frieden I Esterly Northward

Neonatal Dermatology

, second ed.

Philadelphia, PA

:

Saunders

;

2008

:

131

–

158

24

Bruckner A

Epidermolysis Bullosa

. In: Eichenfield L Frieden I Esterly N

Neonatal Dermatology

, 2nd ed.

Philadelphia, PA

:

Saunders

;

2008

:

159

–

172

25

Hollmann TJ Brenn T Hornick JL

CD25 expression on cutaneous mast cells from adult patients presenting with urticaria pigmentosa is predictive of systemic mastocytosis.

Am J Surg Pathol

.

2008

;

32

(

one

):

139

–

145

26

Brockow K

Epidemiology, prognosis, and risk factors in mastocytosis.

Immunol Allergy Clin North Am

.

2014

;

34

(

2

):

283

–

295

27

Lazar A Murphy G

The Skin

. In: Kumar Five Abbas A Aster J Fausto N

Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Ground of Affliction

, 8th ed.

Philadelphia, PA

:

Saunders

;

2009

:

2293

–

2296

28

Tharp Chiliad

Mastocytosis

. In: Bolognia J Jorizzo J Schaffer J

Dermatology

, 3rd ed.

Amsterdam, Netherlands

:

Elsevier Limited

;

2012

:

1993

–

2002

29

Uzzaman A Maric I Noel P Kettelhut BV Metcalfe DD Carter MC

Pediatric-onset mastocytosis: a long term clinical follow-up and correlation with bone marrow histopathology.

Pediatr Claret Cancer

.

2009

;

53

(

4

):

629

–

634

30

Heide R Beishuizen A De Groot H Dutch National Mastocytosis Work Group

Mastocytosis in children: a protocol for management.

Pediatr Dermatol

.

2008

;

25

(

4

):

493

–

500

31

Simons FE Silas P Portnoy JM

Safety of cetirizine in infants half dozen to 11 months of age: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled written report.

J Allergy Clin Immunol

.

2003

;

111

(

6

):

1244

–

1248

Competing Interests

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF Interest: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Fiscal DISCLOSURE: Dr Lin received support from the KL2 Mentored Career Evolution Honor of the Stanford Clinical and Translational Scientific discipline Accolade to Spectrum (NIH KL2 TR 001083, UL1 TR 001085) and the Clinical Excellence Research Center; the other authors accept indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this commodity to disembalm.

Copyright © 2018 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

2018

Citing articles via

Email alerts

Source: https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/141/3/e20170236/37620/Well-Appearing-Newborn-With-a-Vesiculobullous-Rash

Comments

0 Comments

Comments Icon Comments (0)